How Important Is Domain Expertise in Building a B2B Public Company? The Evidence Is … Mixed

"Domain expertise can be a superpower—or a set of blinders."

Some of our most compelling B2B and SaaS founders built their companies from deep domain expertise. Others stumbled into their markets almost by accident. In the middle, some sort of knew their space, but the journey was an entirely new one.

Which is better in B2B? Both approaches can work spectacularly well. At least … in different domains and at different time.

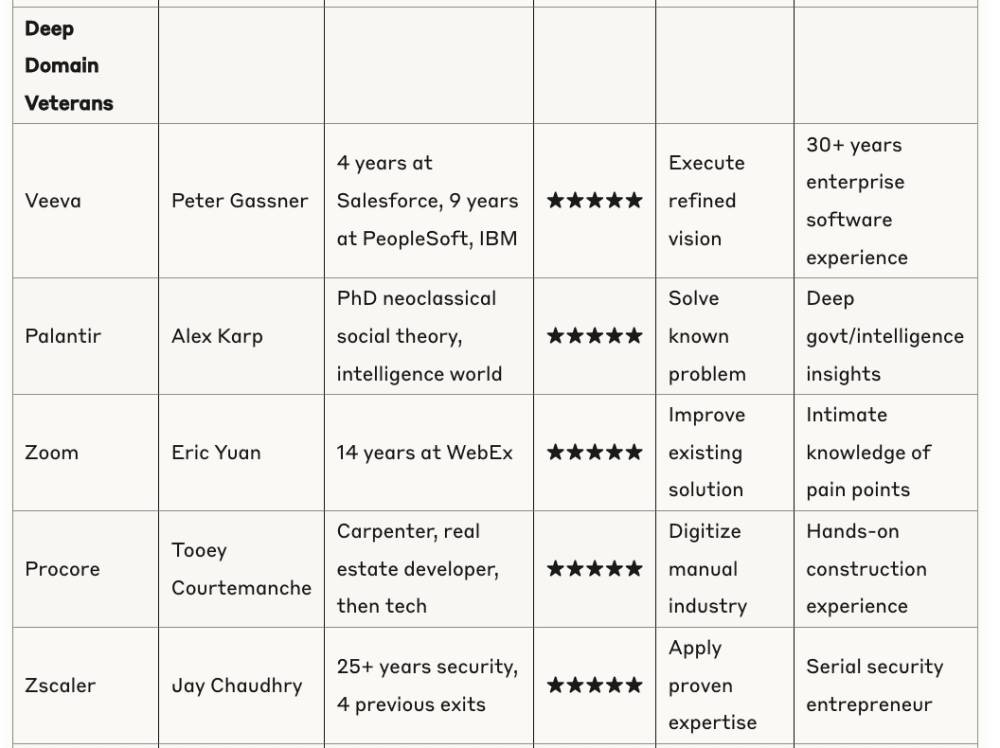

The Deep Domain Veterans

Peter Gassner (Veeva) is the textbook case for domain expertise. He spent 4 years as Senior VP of Technology at Salesforce, 9 years at PeopleSoft as Chief Architect, and started his career at IBM working on mainframes. When he founded Veeva in 2007, he wasn’t exploring—he was executing on a vision refined through decades of enterprise software experience, specifically recognizing that life sciences needed specialized cloud solutions.

Alex Karp (Palantir) came from the intelligence and government world with a unique blend of domain expertise. He has a PhD in neoclassical social theory from Goethe University Frankfurt, where he studied under specialists in German philosophy and worked at the Sigmund Freud Institute. When he co-founded Palantir in 2003 with Peter Thiel, it was born from deep insights into post-9/11 national security needs and the belief that Silicon Valley should be involved in fighting terrorism while protecting civil liberties.

Eric Yuan (Zoom) knew video conferencing inside and out. He’d spent 14 years at WebEx, watching the pain points, understanding the technical challenges, seeing where the market was heading. When he started Zoom, he wasn’t exploring—he was executing on a vision refined over years of direct experience.

Tooey Courtemanche (Procore) combines deep construction domain expertise with tech background. He “started his career as a carpenter and served as a real estate developer” before moving into software. When building his home in Santa Barbara, Courtemanche saw firsthand “how disconnected the construction process could be” and realized he could apply his technology background to solve construction industry problems. His hands-on construction experience gave him unique insight into the pain points that purely technical founders might miss.

Jay Chaudhry (Zscaler) is the quintessential serial security entrepreneur with “more than 25 years of security industry expertise” at IBM, NCR, and Unisys. Before founding Zscaler in 2008, he had already founded and successfully exited four security companies: SecureIT (acquired by VeriSign in 1998), CipherTrust (acquired for $274M in 2006), CoreHarbor (acquired by AT&T), and AirDefense (acquired by Motorola). When he founded Zscaler, he wasn’t exploring a new market—he was applying decades of deep cybersecurity knowledge to solve the cloud security challenge.

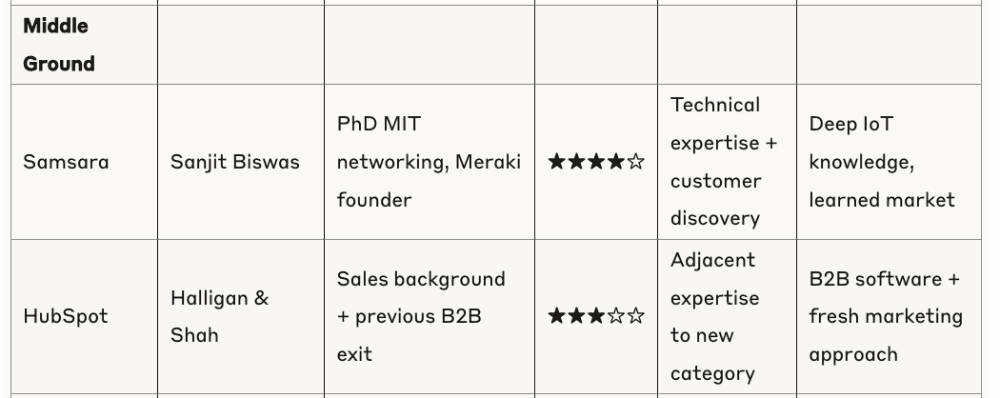

The Middle Ground

Sanjit Biswas (Samsara) represents an interesting hybrid case. He had deep technical expertise in networking and IoT from his PhD research at MIT (Roofnet project) and founding Meraki, which Cisco acquired for $1.2B. But when he started Samsara in 2015, he admitted “no one was building technology for” the physical operations world. He understood the technical infrastructure deeply but discovered the fleet management opportunity through customer conversations, saying food and beverage suppliers “told us about trucking” after seeing his temperature sensors.

Brian Halligan and Dharmesh Shah (HubSpot) represent an interesting case where they brought adjacent domain expertise to a new market. Halligan came from sales and growth background at PTC, while Shah had built and sold Pyramid Digital Solutions, “an enterprise software startup in the financial services sector” focused on “retirement plan industry” software that was “acquired by SunGard Business Systems” in 2005. While they weren’t marketing experts, they understood B2B software and recognized that traditional outbound marketing wasn’t working. They coined “inbound marketing” by combining Shah’s successful blogging during business school with Halligan’s observations about failing traditional tactics.

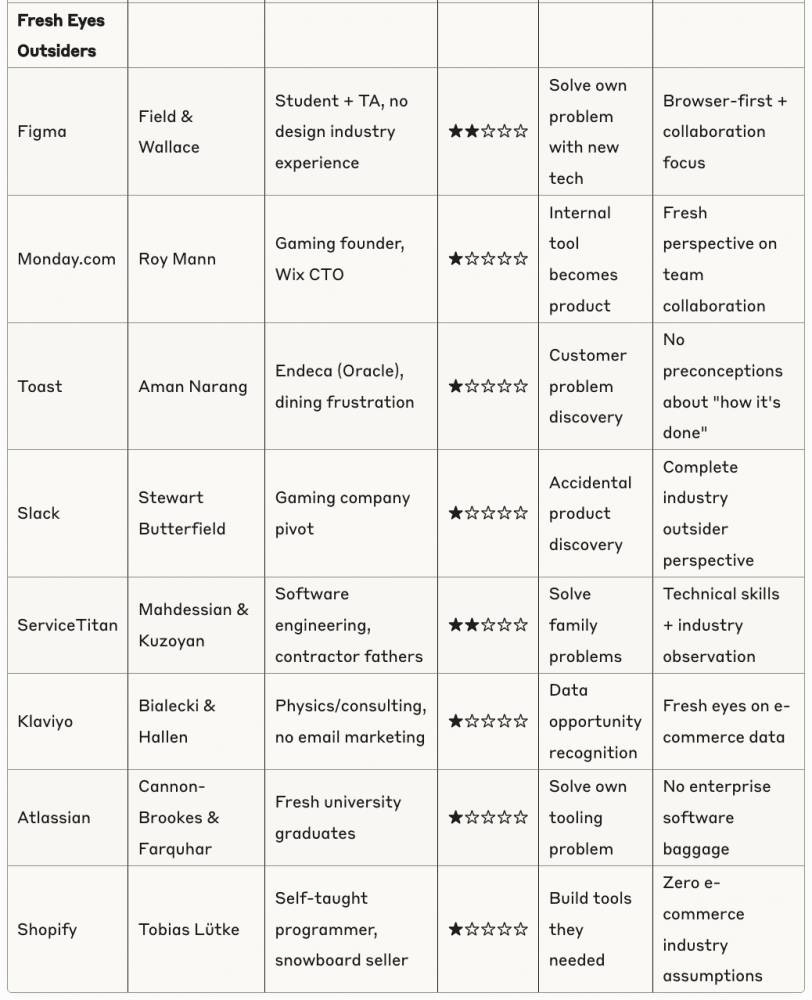

The Fresh Eyes Outsiders

Roy Mann and Eran Zinman (Monday.com) represent the classic “accidental founder” story. Monday.com started as an internal tool at Wix called “Dapulse” to solve communication problems as Wix scaled. Mann was CTO at Wix and had previously founded a gaming company called SaveAnAlien. He had zero experience in project management software—just a fresh perspective on how teams should collaborate.

Dylan Field and Evan Wallace (Figma) epitomize the “solve your own problem” approach with a technical twist. Field was a computer science student at Brown who had worked as an intern at LinkedIn and Flipboard, while Wallace was his teaching assistant with deep graphics expertise. When they started experimenting with browser-based design tools in 2012, they had zero experience in the design software industry. Field’s original vision was to “make it so that anyone can be creative by creating free, simple, creative tools in a browser.” They tried many different ideas first—including software for drones and even a meme generator during what Field calls “the darkest week of Figma”—before settling on collaborative design tools. With a $100,000 Thiel Fellowship grant, they dropped out of college to build what became the dominant interface design tool, eventually going public at a $68 billion valuation. They succeeded not because they knew the design industry, but because they saw collaboration and browser-based tools with completely fresh eyes.

Aman Narang (Toast) and his co-founders epitomize the outsider approach. The idea came while dining out in Boston—they were frustrated waiting for their check and wished they could pay with their smartphone. They had worked together at Endeca (acquired by Oracle) but had “very little experience running a startup” and weren’t restaurant industry veterans. As Fredette admits, “Not having spent a lot of time in the restaurant industry ourselves, we didn’t presuppose we knew what our customers needed”.

Stewart Butterfield (Slack) epitomizes the fresh eyes approach. Slack emerged from Tiny Speck, a gaming company building an online game called Glitch. When the game wasn’t working, they realized their internal communication tool was more valuable than the game itself. Butterfield had no enterprise software background—he was focused on gaming and design—but saw team communication with completely fresh eyes.

Ara Mahdessian and Vahe Kuzoyan (ServiceTitan) epitomize the “solve your parents’ problems” approach. Both studied software engineering (Stanford and USC respectively) but had zero experience in home services business software. Their fathers were contractors—residential and plumbing—and they watched them “work long days in the field, and long nights back at home managing the business” with manual processes. As immigrants’ sons, they built ServiceTitan because they saw an industry “frozen in time” while other sectors had embraced technology.

Andrew Bialecki and Ed Hallen (Klaviyo) spotted an opportunity in e-commerce marketing despite having no email marketing background. Bialecki studied Physics, Astronomy and Astrophysics at Harvard, while both worked at Applied Predictive Technologies doing consulting. They founded Klaviyo in 2012 after realizing “consumer brands were sitting on mountains of data but couldn’t use it to personalise experiences or drive revenue.” Bialecki coded every line himself for the first five years, learning email marketing through building the product.

Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar (Atlassian) epitomize the “accidental billionaire” story. They were fresh university graduates from University of New South Wales who “founded Atlassian with the aim to replicate the A$48,500 graduate starting salary typical at corporations without having to work for someone else.” They started providing customer support services but were frustrated with the bug-tracking software they were using. So they built Jira and “quickly decided they were better off selling Jira than providing support services.” They had no experience in enterprise software or development tools—they just solved their own problem and discovered a massive market.

Tobias Lütke (Shopify) represents the ultimate “solve your own problem” founder. A self-taught programmer who dropped out of school at 16, he moved from Germany to Canada in 2002 and wanted to sell snowboards online. “Dissatisfied with the existing e-commerce solutions,” he built his own platform using Ruby on Rails for his snowboard shop Snowdevil. After one season, he realized “the e-commerce software he’d built had more potential than the snowboard brand itself” and pivoted to selling the platform rather than snowboards. He had zero e-commerce industry experience—just a programmer who needed better tools.

The Universal Success Factors

Regardless of your starting point, the fundamentals remain the same:

Keep going. Gassner spent years at Salesforce identifying the vertical cloud opportunity before founding Veeva. Toast’s founders spent nine months coding in Narang’s basement before getting traction. Persistence matters more than perfect timing.

Don’t quit. Both insiders and outsiders face the valley of death. Domain experts get told “it’s been tried before.” Outsiders get told “you don’t understand the market.” Both are wrong—if you don’t quit.

Hire great people. Gassner emphasizes getting “people from different types of backgrounds, different types of companies. Don’t be too myopic in where you hire from”. Domain experts need fresh perspectives on their teams. Outsiders need domain expertise.

Don’t run out of money. Veeva achieved a $400M run rate on just $3M in capital by being ruthlessly efficient. Toast founders were so inexperienced with fundraising they would “debate each other during investor meetings”, but they managed their runway carefully.

The Real Insight

Many of the most successful founders combine both approaches. HubSpot’s Halligan notes they had “a healthy disrespect for conventional wisdom”, while Veeva’s Gassner methodically built on 30 years of enterprise software experience.

Domain expertise can be a superpower—or a set of blinders. Fresh eyes can spot obvious opportunities—or miss critical complexities. As Toast’s team discovered, “We were always very customer-driven… the best way to figure out what to build was to work with customers and deeply understand their problems”.

The Bottom Line

The market doesn’t care about your background. It cares about whether you solve real problems for real people willing to pay real money.

Whether you’re a 20-year industry veteran like Gassner or accidentally discovered your market like the Monday.com team, focus on the fundamentals. Build something people want. Keep iterating. As HubSpot’s founders learned, “Word-of-mouth is not a function of how much revenue you’re making from a customer. Word-of-mouth is how many people out in the world love your product so much that they want to tell someone else about it”.

The rest is just storytelling.